On March 22, 2024, the Cyberspace Administration of China officially released the Provisions on Facilitating and Regulating Cross-border Data Flow (effective on the same day, the "New Regulations on Cross-Border Data Flow"). On the same day, the Cyberspace Administration of China also published the updated Guide to Applications for Security Assessment of Outbound Data Transfers (Second Edition), Guidelines for Filing the Standard Contract for Outbound Cross-Border Transfer of Personal Information (Second Edition) and other documents including press release Q&As.

The National Cyber Security Standardization Technical Committee also released the Data Security Technology — Rules for Data Classification and Grading (draft for approval) (GB/T 43697-2024, the "New Classification and Grading Regulations"; in this article, the New Classification and Grading Regulations and the New Regulations on Cross-Border Flow are collectively referred to as the "2024 Data New Regulations"), which will be implemented on October 1, 2024.

1. Background of the 2024 Data New Regulations

Since 2021, laws and regulations such as the Personal Information Protection Law have established three main pathways for the outbound transfer of data and personal information in China: security assessments organized by national cyberspace authority ("Security Assessments"), personal information protection certification conducted by professional institutions ("Certification"), and contracts with overseas recipients based on standard contracts formulated by the national cyberspace authority ("Standard Contracts", collectively "Data Outbound Transfer Procedures").

With the establishment of these procedures, various guidelines and rules have been issued, such as the Data Transfer Security Assessment Measures (effective 2022), the Cybersecurity Standard Practice Guidelines—Security Certification Specifications for Cross-Border Processing of Personal Information (v1.0 and v2.0 both released in 2022) and the Measures for the Standard Contract for Outbound Cross-Border Transfer of Personal Information (effective 2023), moving China’s Data Outbound Transfer Procedures into the implementation stage. There have been cases of successful security assessments and standard contract filings across the country. To further regulate and promote the lawful and orderly free flow of data, the Cyberspace Administration of China published a draft of the Provisions on Facilitating and Regulating Cross-border Data Flow (the "New Regulation on Cross-Border Flow (Draft for Comments)") for public comments on September 28, 2023. After its publication, the industry made various speculations on the future regulations, awaiting its formal adoption. The Provisions on Facilitating and Regulating Cross-border Data Flow were officially issued and took effect on March 22, 2024, marking a new era for the regulation of outbound transfer of data and personal information in China. Concurrently, the New Classification and Grading Regulations provide detailed guidance to the industry, the local authorities and data processors on the establishment of data classification and protection systems required by laws and regulations such as the Data Security Law.

2. Main Contents of the New Regulations on Cross-Border Flow

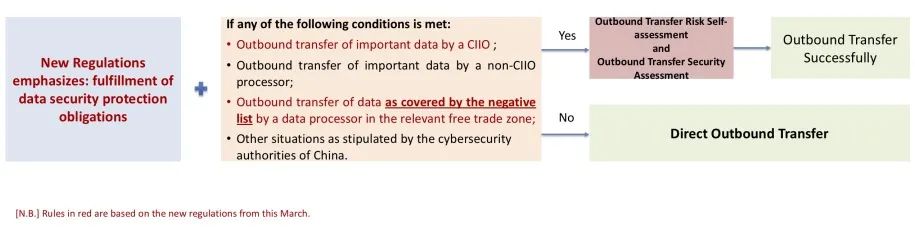

Although the New Regulations on Cross-Border Flow only contains 14 articles, it adjusts and refines the operational threshold, exemptions, procedural matters, and regulatory requirements of the data outbound transfer procedures from a procedural perspective. As the wording of the new regulations are relatively direct, and the practitioners are generally familiar with the previous draft version, we will summarize the main contents and process of personal information and data cross-border transfer as shown in the following charts (with new/adjusted contents highlighted in red).

Chart 1: Outbound Transfer of Personal Information

Chart 2: Outbound Transfer of Data (Other than personal Information)

3. Questions to be Clarified.

The biggest advancement of the New Regulations on Cross-Border Flow is that it provides a series of exemptions where no data outbound transfer procedure is required. However, while many of the legal profession practitioners applaud that it will now be more direct and convenient for clients’ data to be transmitted abroad, we note that there are still some practical difficulties that require clarification:

(1) How to Deal with the Situation where certain Data is Announced or the Data Processor is Notified that such Data is Important After it has been Transmitted Abroad?

Under the New Regulations on Cross-Border Flow, regardless of the outbound transfer scenario or scale of the data transferred, any important data transmitting out of the country still needs to undergo an outbound transfer risk self-assessment and a security assessment. According to Article 2 of the New Regulations on Cross-Border Flow, unless the data is announced or published by relevant department or local authority as important data, data processors are not required to apply for the security assessment for such data. At this stage, only a handful national level departments or regional authorities have issued catalogs of important data in their charge. This greatly reduces the concerns of many companies about touching the “red line” of important data.

However, we believe this provision does not constitute an absolute "safe harbor" for all data processors. It does not explicitly exempt all types of data outbound transfer activities that occurred before this new regulation took effect in a retroactive manner. Additionally, under the New Regulations on Cross-Border Flow, can data processors arrange to transmit the data they process or control outside the country without formally clarifying with the relevant regulatory departments first? The risk of misjudging whether data is important essentially lies with the data processors themselves.

Based on existing regulations related to important data (including the New Classification and Grading Regulations), we believe that data processors still cannot sit back and relax without considering this important data determination issue and freely transmit their data abroad.

(2) How to Determine Data Outbound Transfers that Do Not Include Personal Information Collected or Generated in China?

Article 4 of the New Regulations on Cross-Border Flow lists "the outbound transfer of personal information collected and generated overseas by data processors, which had been transferred to and processed in the territory of China" as an exempted scenario. This scenario seems easy to understand: personal information collected abroad merely "stops by" or "transits" domestically before leaving the country.

However, how is "domestic personal information" defined? Should the standard be based on the individual’s nationality or their location? For example, for foreigners living in China, if the processing of personal information occurs during their stay in China, does their information also constitute "domestic personal information"? Or if the personal information processed and collected abroad comes from people of Chinese nationality living abroad, does the "data transit" exemption still apply?

In practice, for cross-border e-commerce, B2C e-commerce, or SAAS service scenarios, personal information data packages in "data transit" may include personal information of Chinese nationals collected abroad, and personal information of foreigners in China may need to added during transit. These are common practices in e-commerce and cross-border business scenarios. How to correctly apply this exemption to these business scenarios remains to be answered.

(3) How to Determine the "for the Purpose of Executing and Performing a Contract" Exemption?

Article 5 (1) of the New Regulations on Cross-Border Flow stipulates that if it is truly necessary to transfer any personal information overseas for the purpose of executing and performing a contract to which the individual is a party concerned, such as cross-border shopping, cross-border consignment, cross-border remittance, cross-border payment, cross-border account opening, air ticket and hotel reservation, visa application, and examination services, the transfer is exempted from undergoing data outbound transfer procedures.

The practical issue lies in determining who the exempted party is: (i) the individual who directly signs a contract with the foreign service/product provider and provides their personal information, or (ii) the domestic enterprise that enters into an intermediary or other service contract with the domestic individual, then transmits such individual’s information to the foreign entity that actually provides the product/service.

The premise of Article 5 of the New Regulations on Cross-Border Flow is "data processors provide personal information overseas," and one of the legal bases of the data outbound transfer procedure—Article 38 of the “Personal Information Protection Law”—stipulates that the prerequisite for conducting a data outbound transfer procedure is "it is necessary for personal information to be provided by a personal information processor to a recipient outside China due to any business need or any other need." Therefore, the regulated subject of outbound transmission should be the personal information/data processor. Should the domestic individuals themselves be considered the processor of their own information?

For this question, a guideline[ii] on GDPR issued by the European Data Protection Board clarifies that the act of data receivers directly receiving data from data subjects (similar to the concept of “domestic individuals” under Chinese law) within the EU does not constitute data cross-border transmission; hence such data does not need to comply with GDPR’s requirements for cross-border data compliance. Thus, from a comparative law perspective, under GDPR, the aforementioned scenario (i) should not be regulated by personal information and data outbound transfer laws; as a domestic individual, providing their personal information abroad should constitute the individual choosing foreign services or goods in his/her freewill.

Can we infer that the above scenario (ii) also constitutes an absolute "safe harbor" for domestic personal information processors including airlines, travel agencies, domestic banks, cross-border e-commerce companies, etc. to provide overseas subjects that actually provide the products/services with China’s personal information? Due to lack of published real cases and clear legal guidance, we can only doubt this conclusion at present.

It is important to note that this questionable "safe harbor" clause might also be abused in scenarios where sensitive personal information (such as bank account financial information) is transferred abroad. There might be conflicts or overlaps with scenarios that require certification or standard contracts (transferring sensitive personal information of less than 10,000 people abroad) and scenarios that require security assessment (transferring sensitive personal information of more than 10,000 people abroad). How to distinguish and apply the rules? This is another difficult question faced by domestic processors of sensitive personal information, especially cross-border e-commerce companies and travel agencies.

(4) How to Implement the "Human Resources Management" Exemption?

Article 5(2) of the New Regulations on Cross-Border Flow stipulates that where it is truly necessary to transfer any personal information of an internal staff member overseas for the purpose of cross-border human resources management under lawfully established labor rules and regulations and pursuant to a lawfully executed collective contract, the transfer is exempt from undergoing data outbound transfer procedures. This provision significantly eases the burden of multinational companies and other enterprises engaged in cross-border human resources management.

However, we note that the phrase "under lawfully established labor rules and regulations and pursuant to a lawfully executed collective contract" is condition for processing personal information as set out in the second paragraph of Article 13 of the Personal Information Protection Law, which also uses the conjunction "and." Therefore, if a domestic enterprise, as data processor, wishes to use this exemption, must it incorporate the outbound transfer of personal information into its lawfully established labor rules and regulations and its lawfully executed collective contract? Apart from the labor rules familiar to most enterprises, the process of signing collective contracts could be relatively complex for some. According to the Labor Contract Law, a collective contract shall be concluded by the labor union, representing the enterprise employees, and the employer. If the employer has not established a labor union, it shall conclude the contract with a representative nominated by the employees under the guidance of the labor union at the next higher level. After a collective contract is concluded, it shall be submitted to the labor administrative department. The collective contract shall become effective only if the labor administrative department does not raise any objection to the contract.[iii] From the perspective of ease of implementation, can these two actions be interpreted in an "or" relationship? Moreover, how should enterprises demonstrate the "necessity to provide employees’ personal information abroad"? Can enterprises argue that establishing a local HR management system alone cannot effectively support local operations? These questions remain to be clarified.

Furthermore, does "employee" under this article narrowly include only those who have directly signed labor contracts with the domestic data processor? If personal information of employees under labor dispatch or service contracts arrangements needs to be transferred abroad, does it not qualify for this exemption?

For example, under the structure of foreign enterprises/institutions’ representative offices in China, Chinese "employees" are employed under a third-party labor dispatch arrangement; such representative offices (not legal entities) might in practice have a strong need to transfer domestic "employees" personal information (e.g., for salary and benefits management) to their headquarters abroad. Are they qualified for this exemption? This remains a question.

(5) How to Implement the Free Trade Zone Negative List?

A major highlight of the New Regulations on Cross-Border Flow is Article 6, which allows pilot free trade zones to independently formulate a list of data to be included in the data outbound transfer management procedures (the "Negative List") for the said free trade zone. For any outbound transfer of the data not under the Negative List by data processors in the pilot free trade zone, the data outbound transfer procedures are exempted.

Recently, some pilot free trade zones, represented by the China (Shanghai) Pilot Free Trade Zone, have issued measures/regulations to facilitate cross-border data transfers. For instance, the Lingang Special Area released the China (Shanghai) Pilot Free Trade Zone Lingang Special Area Administrative Measures of Classification and Grading of Cross-Border Flow of Data (for Trial Implementation) (the "Lingang Administrative Measures"). This method differentiates data outbound transfer procedures based on data classification: core data is prohibited from outbound transferring; for data listed in the important data directory, a security assessment can be applied for through the Lingang Special Area Data Cross-Border Service Center; for data listed as general data, registration and filing can be applied for with the Lingang Special Area Management Committee, allowing free flow of data under relevant management requirements. Currently, the important data directory and general data list of the Lingang Special Area have not been officially published. Similarly, according to public sources, no pilot free trade zone has released its official Negative List.

Considering the characteristics of data processing, its geographical nature can be vague, making it difficult to distinguish from a "territorial" or “in rem” perspective. In practice, a data processor registered within a pilot free trade zone might physically locate its data processing servers in another location or even use several servers across regions for data processing. In these cases, how should data processors determine if they are subject to the pilot free trade zone’s Negative List and how to determine the scope of data they can process?

We note that the Lingang Administrative Measures applies to (i) data processors registered within Lingang Special Area or (ii) those conducting data cross-border transfer activities within the Lingang Special Area. Based on this, can companies registered in the Lingang Special Area under scenario (i) conduct general data cross-border transmission nationwide? Additionally, how to determine if data cross-border transmission activities under scenario (ii) take place within the Lingang Special Area? Does scenario (ii) imply that only general data transmitted abroad via servers within the Lingang Special Area can enjoy this exemption?

The questions discussed above are not exclusive. The implementation of the pilot free trade zone’s Negative List awaits further clarifications.

4. Contents and Challenges of the New Classification and Grading Regulations

As mentioned previously, with the release of the New Regulations on Cross-Border Flow, the New Classification and Grading Regulations also provides clearer guidance for enterprises on data compliance.

Before the issuance of the New Regulations on Cross-Border Flow, there had been some national, local, and industry-level standards, rules, guidelines, and related drafts for comments. The New Classification and Grading Regulations have absorbed and referenced the content of these documents, with updates and adjustments.[iv] Besides the usual contents, including scope, cited documents, terminology, and definitions, the New Classification and Grading Regulations also systematically summarizes the basic principles of data classification and grading, rules for data classification (framework and methods), rules for data grading, and the process of data classification and grading. Notably, it includes ten appendices, providing a wealth of factors, examples, guidelines, and references for data classification and grading. We will not go into the details in this article; however, we will discuss a few practical challenges based on the New Classification and Grading Regulations for discussion:

(1) Understanding the Qualitative and Quantitative Aspects in Data Grading

In previous classification and grading rules, the standards of classification were guided by various qualitative properties. However, in practice, enterprises often need to make judgments based on actual scenarios, typically requiring a quantitative perspective assessment. Although sections like Appendix F "Impact Degree Reference Examples" in the New Classification and Grading Regulations provide examples of indicators such as the number of people affected, overall, the New Classification and Grading Regulations still lack refinement in quantitative aspects.

For instance, although in Appendix H "General Data Grading Reference," criteria such as causing "general/serious/very serious harm" to personal or organizational rights are mentioned, but it is difficult to quantify such adjectives. Enterprises might need standards that allow quantification of harm in terms of possible economic losses or the range of affected businesses/populations.

(2) Dealing with Diverse Industry Grading Standards

In considering grading, there might be multiple dimensions involved. As previously mentioned, different industries/government departments and regions may have varying regulatory requirements for grading the same matters. How should enterprises manage their data in a multidimensional regulatory environment? The New Classification and Grading Regulations propose a principle of adopting the highest and the strictest standard in grading data. When multiple factors may influence data grading, the grade is determined based on the highest degree of influence. However, enterprises still need to make comprehensive judgments based on their actual circumstances.

For example, the Measures for Data Security Management in the Industrial and Information Technology Sector (for Trial Implementation) classifies data into general, important, and core data. In contrast, the Financial Data Security Data Security Grading Guide (JR/T 0197—2020) divides financial industry data into five levels. When the same data involves attributes of two industries, the grading under different factors might significantly vary.

(3) How to Deal with the Contradictions that Different Classification Standards may apply to the Same Data?

Based on the New Classification and Grading Regulations, enterprises must also apply specific industry and regional classification and grading standards. These standards, proposed by regional and industry regulatory authorities from a macro and regulatory perspective, are intended to apply to various scenarios. Yet, when enterprises implement these standards, differences in specific situations among enterprises might require case-by-case analysis.

For example, the Financial Data Security Data Security Grading Guide (JR/T 0197—2020) categorizes the affected subjects into national security, public interest, personal privacy, and corporate rights. If a commercial bank serves a large state-owned enterprise, the financial data it obtains may be used in multiple scenarios. It may still be a challenge for the bank to judge whether data rises to the level of national security, public interest, or corporate rights based on general regulations.

(4) How to Sort Out Dynamic Data?

When enterprises sort out data by themselves, enterprises can follow the New Classification and Grading Regulations’ principles of comprehensiveness and dynamic update. However, given the nature of data and technological limitations within such companies, this often requires significant efforts. Data sources vary (departments, devices, external resources, etc.), making it challenging for enterprises to easily manage from a comprehensive perspective. For instance, static user data might be of a lower level when used alone but could become higher level when combined with other data. Enterprises might struggle to categorize data through simple extraction of words, potentially requiring further assistance from appropriate technological means.

5. Conclusion

It is encouraging to see that the newly issued New Regulations on Cross-Border Flow and the New Classification and Grading Regulations have provided some regulatory relaxation and detailed guidance for enterprises, which will help enterprises better carry out their data transfer and improve their management of data and personal information. However, enterprises should not interpret this as a signal that they can rest easy on data compliance management. The questions we raised in this article may only represent a fraction of the challenges enterprises face in practice, which might point to the right direction for continuous improvements by various personal information and data processors and regulatory authorities in charge.

[i] Intern Victoria Liao has also contributed to this article.

[ii] Guidelines 05/2021 on the Interplay between the application of Article 3 and the provisions on international transfers as per Chapter V of the GDPR.

[iii] Article 51 and Article 54 of the Labor Contract Law.

[iv] Especially the Cyber Security Standard Practical Guidance Cyber Security Classification and Grading Guide published by Secretariat of the National Information Security Standardization Technical Committee (the New Classification and Grading Regulations overlaps with it in structure and content).